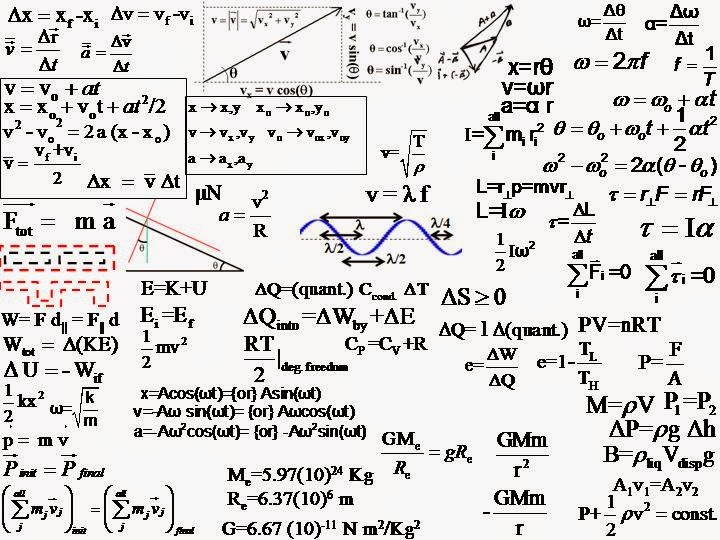

I stare stunned as, on the blackboard, the professor writes a scientific formula that stretches into its third line of squiggles and numbers. He spews incomprehensible narration of what sounds like chemistry, physics of light, and astrophysics.

Was this science course listed as non-prerequisite? I must complete a single science requirement this last semester for my M.A. in Economics. When I graduate in three months, I will leave my husband, take my two babies, and move to the city where the jobs are. Without a science course, I’ll lose my investment of four years and money I can ill-afford.

At the blackboard, the professor explains how to measure the temperature of a mass of compact matter called “a star” based upon its thermonuclear fusion, and then shows how to extrapolate in the process how old this star is and how many eons will it live before its supernova nucleosynthesis. The kinematic viscosity is helpful here, and don’t forget the hydrostatic equilibrium, of course.… No science prerequisite? When I signed for Cosmology, I thought of Astronomy. I could already point out the Great Dipper and Orion, but would flaunt new expertise about constellations at a beach party on dark summer nights….

At recess, I stop at the professor’s desk. He is munching on a sandwich.

“Professor, this class was listed specifically as one with no science prerequisite.”

“Do you have high school math?”

I nod.

“Well then, you have all the background you need.”

I point at the blackboard. “Not this—”

His hand waves in dismissal. “Cosmology is fun.” He gulps coffee from his thermos. “Trust me. You’ll be okay.”

After everyone has written their names on the yellow legal pad, introductions are made. Of the over thirty students, I am the only one who is not a science teacher, a Brookhaven nuclear lab worker, or an engineer taking this “safe” course for a graduate management degree.

Before next week’s class I verify that none of the university’s other science classes is listed with no prerequisite. They must all be worse than this Cosmology business. Besides, this class is scheduled in the evening, off campus, closer to my house. It’s difficult to pay for a babysitter and gasoline these days when my husband is MIA, yet suing for custody of my babies, and my legal fees have already depleted my parents’ savings.

I can only switch classes in the first two weeks of the semester. It’s now or never. My entire future is on the line. Therefore, when in the second lecture the professor explains why Einstein’s Law of Relativity does not apply to cosmos, I plant myself in front of his desk at recess. I wait until he passes around the yellow legal pad for all to sign attendance.

“Professor.” My eyes filled with tears. “I don’t know why Einstein’s Law of Relativity works on our Planet Earth. How can I figure out why it doesn’t elsewhere? This class is for scientists.”

“High school math is all you need,” he repeats.

“If I don’t drop out today, I won’t be able to get into another course.” I place in front of him the printout of the school program. “Can you suggest another one for a lay person?”

“Look.” He picks something caught between two molars. “I believe that if you just sit in class and listen, you’ll get it.”

I am certain that if I lay in the river for months I won’t turn into a crocodile. I shake my head. “No way.”

“I’ll make a deal with you,” he says. “If you just show up for all classes, I’ll give you a B.”

Just like that? “What about the quizzes and the semi-final and final exams?”

“You’ll get a B. Just for attending.”

Maybe it doesn’t look good for him when people drop out, but I am willing to buy the arrangement. Off the hook, I take a jaunty jig to my seat.

For the rest of the semester,

I ignore the two multi-choice quizzes in which I fail, followed by the mid-term.

I also do not attempt to decipher the formulas the professor scribbles on the

blackboard. I am light-years away from caring what happens to helium at 40,000

degrees Fahrenheit or calculating the velocity of matter gravitating toward a

nebula (what’s that?) by converting the heat volume to light units. Or perhaps,

the reverse deduction? Oh, yes, all these pieces of data also tell us how old

the star is. Or is it a planet? Calculate it all, please, with your high school

math. Did I mention distance? It can be extrapolated from this data if we also

add the color of the light of a given star because it can be deduced from its

electromagnetic spectrum….

That is Cosmology. The science to top all sciences because it includes all of them.

I show up every Wednesday at seven in the evening and sit down to doodle. The only thing I learn is that quantum mechanics and molecular physics are also incorporated into the formulas on the blackboard. It doesn’t matter, really. I will get a B. At recess, I sign my name on the yellow legal pad, then leave and go home to my babies and to study for the other classes I must complete. Actually, my home is no longer “my home,” as I have escaped domestic violence, and we now sheltered in someone’s basement. Soon, I’ll finish this semester and begin a new life far from here.

Three weeks to finals. A judge with an unabashed dislike of women wishing to liberate themselves grants me only twenty-five dollars a week for the three of us. If not for the kindness of strangers, we’d starve. I polish my resume and start applying for jobs.

I stop at the professor’s desk. “Remember our agreement?” I ask. “I don’t need to do well on the final. I get a B.”

“Oh, no,” he replies. “The agreement was for you to sit in the classroom. You left every week at recess.”

The hair roots stand on my head. A split second later, the blood drains from my temples. “You can’t do this,” I whisper. “I can’t graduate with less than a B.”

“Sorry. That was the deal.”

I begin to hyperventilate.

His sympathy must be genuine because he says, “Look. If you get an A, I will ignore all these failed quizzes and the mid-term.”

“An A?” I blurt like a dimwit.

“I’m giving you a new deal.”

I walk away in a daze. My celestial fantasies of a life outside the doomed marriage is sucked into the kind of black hole the professor talked about, some mass so compacted that nothing escapes from it, not even light.

There is no choice. I must get an A in Cosmology as if my life depends on it, because it really does.

I go to the public library and plant myself in the children’s section. I begin reading first-grade books about planets and novas and black holes. I study the colorful pictures of the expanding universe and read about stellar dynamics and galaxies and what they are made of. Junk, really, clouds of particles and gasses—hydrogen and helium mostly—that under high pressure change from one chemical composition into something else whose density can be measured using luminosity and temperature.

Equipped to put it all in some context, I move to middle-school level books. I should be able to learn material suitable for a ten-year old, even a fourteen-year old. The Big Bang theory; the Hubble telescope; white and red dwarfs; isometric theory; gravitation; black spaces; nuclear fission. Artists’ renderings are very helpful. I begin to get it. Presented in a way I can understand, the material piques my curiosity. Suddenly, I even enjoy it. Coming out of the library late on a moonless night, I look at a pinprick of a star in the sky and know that I am staring at history: this light left its source eons ago, but only now it reaches my human eye here on earth. How awesome is that?

I am soon in the library’s high school science section, then check another library to make sure I cover all available easy books. I have no idea what material was taught in class; to be on the safe side I read everything.

By the end of an intensive three weeks, I close the last page of The Encyclopedia of Cosmology, having read every value in it. To my bewilderment and surprise, I comprehend it all.

The transcript of my grades arrives. Scared, I hold the envelope in my palm. I’ve already moved my family. I glued stickers of galaxies and constellations on the ceiling of my babies’ new bedroom. My lawyer guaranteed the first two months’ rent, uncertain how I would pay it. I’ve taken the first semi-decent marketing job offered. The unknown, the responsibility, and the fear bear down on me so much that I’ve lost the grip on who I am.

I open the envelope.

Cosmology: A.

In the decades that have passed since my last exam, I’ve stared many times into the depth of the Milky Way. I know that our galaxy is merely one of hundreds of billions other galaxies, but rather than feel small, I feel victorious: I explored the farthest reaches of our vast, ever-expanding universe and came out a winner.

# # #

Author Talia Carner’s heart-wrenching suspense novels,JERUSALEM

MAIDEN , CHINA

That is Cosmology. The science to top all sciences because it includes all of them.

I show up every Wednesday at seven in the evening and sit down to doodle. The only thing I learn is that quantum mechanics and molecular physics are also incorporated into the formulas on the blackboard. It doesn’t matter, really. I will get a B. At recess, I sign my name on the yellow legal pad, then leave and go home to my babies and to study for the other classes I must complete. Actually, my home is no longer “my home,” as I have escaped domestic violence, and we now sheltered in someone’s basement. Soon, I’ll finish this semester and begin a new life far from here.

Three weeks to finals. A judge with an unabashed dislike of women wishing to liberate themselves grants me only twenty-five dollars a week for the three of us. If not for the kindness of strangers, we’d starve. I polish my resume and start applying for jobs.

I stop at the professor’s desk. “Remember our agreement?” I ask. “I don’t need to do well on the final. I get a B.”

“Oh, no,” he replies. “The agreement was for you to sit in the classroom. You left every week at recess.”

The hair roots stand on my head. A split second later, the blood drains from my temples. “You can’t do this,” I whisper. “I can’t graduate with less than a B.”

“Sorry. That was the deal.”

I begin to hyperventilate.

His sympathy must be genuine because he says, “Look. If you get an A, I will ignore all these failed quizzes and the mid-term.”

“An A?” I blurt like a dimwit.

“I’m giving you a new deal.”

I walk away in a daze. My celestial fantasies of a life outside the doomed marriage is sucked into the kind of black hole the professor talked about, some mass so compacted that nothing escapes from it, not even light.

There is no choice. I must get an A in Cosmology as if my life depends on it, because it really does.

I go to the public library and plant myself in the children’s section. I begin reading first-grade books about planets and novas and black holes. I study the colorful pictures of the expanding universe and read about stellar dynamics and galaxies and what they are made of. Junk, really, clouds of particles and gasses—hydrogen and helium mostly—that under high pressure change from one chemical composition into something else whose density can be measured using luminosity and temperature.

Equipped to put it all in some context, I move to middle-school level books. I should be able to learn material suitable for a ten-year old, even a fourteen-year old. The Big Bang theory; the Hubble telescope; white and red dwarfs; isometric theory; gravitation; black spaces; nuclear fission. Artists’ renderings are very helpful. I begin to get it. Presented in a way I can understand, the material piques my curiosity. Suddenly, I even enjoy it. Coming out of the library late on a moonless night, I look at a pinprick of a star in the sky and know that I am staring at history: this light left its source eons ago, but only now it reaches my human eye here on earth. How awesome is that?

I am soon in the library’s high school science section, then check another library to make sure I cover all available easy books. I have no idea what material was taught in class; to be on the safe side I read everything.

By the end of an intensive three weeks, I close the last page of The Encyclopedia of Cosmology, having read every value in it. To my bewilderment and surprise, I comprehend it all.

The transcript of my grades arrives. Scared, I hold the envelope in my palm. I’ve already moved my family. I glued stickers of galaxies and constellations on the ceiling of my babies’ new bedroom. My lawyer guaranteed the first two months’ rent, uncertain how I would pay it. I’ve taken the first semi-decent marketing job offered. The unknown, the responsibility, and the fear bear down on me so much that I’ve lost the grip on who I am.

I open the envelope.

Cosmology: A.

In the decades that have passed since my last exam, I’ve stared many times into the depth of the Milky Way. I know that our galaxy is merely one of hundreds of billions other galaxies, but rather than feel small, I feel victorious: I explored the farthest reaches of our vast, ever-expanding universe and came out a winner.

# # #

Author Talia Carner’s heart-wrenching suspense novels,